Summary

Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic surrogate relationships have been used to describe the antibacterial activity of various classes of antimicrobial agents. Studies that have evaluated these relationships were reviewed to determine which of these surrogate markers were further dependent on antimicrobial class.

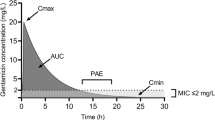

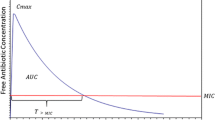

The fluoroquinolone and aminoglycoside agents exhibit concentration-dependent killing. Studies have demonstrated that peak serum concentration: minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and area under the serum concentration-time curve (AUC): MIC ratios are important predictors of outcome for these antimicrobial agents. Area under the inhibitory concentration-time curve (AUIC24) [i.e. AUC24/MIC] is a useful parameter for describing efficacy for these agents, while an adequate peak concentration: MIC ratio seems necessary to prevent selection of resistant organisms.

For β-lactam antibiotics, the duration of time that the serum concentration exceeds the MIC (T > MIC) was the significant pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic surrogate in cases where the bacterial inoculum was low, or where very sensitive organisms were tested. However, in studies using more resistant organisms or larger inoculum sizes there is some concentration-dependence to the observed effect. Studies using reasonable dosage intervals have demonstrated covariance between T > MIC and AUC/MIC ratio for β-lactam antibiotics.

Since glycopeptide antibiotics display relatively slow but concentration-independent killing, and are cell wall active agents similar to β-lactams, it has been presumed that T > MIC is the important pharmacokinetic surrogate related to efficacy for these agents. Some studies have shown that a concentration multiple of the MIC may be necessary for successful outcome with vancomycin. AUIC24 may prove to be an important pharmacokinetic surrogate if both time and concentration are indeed important parameters.

To select an appropriate antimicrobial agent, the clinician must consider many patient-specific as well as organism-specific factors. Utilisation of known pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic surrogate relationships should help to optimise treatment outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Peterson LR, Shanholtzer CJ. Tests for bactericidal effects of antimicrobial agents: technical performance and clinical relevance. Clin Microbiol Rev 1992; 5: 420–32

National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically: approved standard. NCCLS publication M7-A. Villanova: NCCLS, 1985

National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methodology for the serum bactericidal test. 2nd ed. Tentative guideline. NCCLS document M21-T. Villanova: NCCLS, 1990

Leggett JE, Wolz SA, Craig WA. Use of serum ultrafiltrate in the serum bactericidal test. J Infect Dis 1989; 160: 616–23

Dudley MN, Blaser J, Gilbert D, et al. Combination therapy with ciprofloxacin plus azlocillin vs Pseudomonas aeruginosa: effect of simultaneous vs staggered dosing in an in vitro model of infection. J Infect Dis 1991; 164: 499–506

Blaser J, Stone BB, Groner MC, et al. Comparative study with enoxacin and netilmicin in a pharmacodynamic model to determine importance of ratio of antibiotic peak concentration to MIC for bactericidal activity and emergence of resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1987; 31: 1054–60

Craig WA, Redington J, Ebert SC. Pharmacodynamics of amikacin in vitro and in experimental infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 1991; 27 Suppl. C: 29–40

Smith JT. Awakening the slumbering potential of the 4-quinolone antibacterials. Pharm J 1984; 233: 299–305

Schentag JJ, Nix DE, Forrest A. Pharmacodynamics of the fluoroquinolones, In: Hooper DC, Wolfson JS, editors. Quinolone antimicrobial agents. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology, 1993: 259–71

Forrest A, Nix DE, Ballow CH, et al. Pharmacodynamics of intravenous ciprofloxacin in seriously ill patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1993; 37: 1073–81

Dudley MN. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of antibiotics with special reference to the fluoroquinolones. Am J Med 1991; 91 Suppl. 6A: 45S–50S

Hyatt JM, Nix DE, Schentag JJ. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ciprofloxacin against similar MIC strains of S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa using kill curve methodology. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1994; 38: 2730–7

Dudley MN, Mandler HD, Gilbert D, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intravenous ciprofloxacin. Am J Med 1987; 82 Suppl 4A: 363–8

Follath F, Bindschedler M, Wenk M, et al. Clinical efficacy of ciprofloxacin in Pseudomonas infections. In: Neu HC, Wevta H, editors. Proceedings of the First International Ciprofloxacin Workshop. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishing, 411–3

Hackbarth CJ, Chambers HF, Stella F, et al. Ciprofloxacin in experimental Pseudomonas aeruginosa meningitis in rabbits. J Antimicrob Chemother 1986; 18 Suppl. D: 65–9

Shibl AM, Hackbarth CH, Sande MA. Evaluation of pefloxacin in experimental Escherichia coli meningitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1986; 29: 409–11

Leggett JE, Ebert S, Fantin B, et al. Comparative dose-effect relations at several dosing intervals for β-lactam, aminoglycoside and quinolone antibiotics against gram-negative bacilli in murine thigh-infection and pneumonitis models. Scand J Infect Dis 1991; 74 Suppl.: 179–84

Gordin FM, Hackbarth CJ, Scott KG, et al. Activities of pefloxacin and ciprofloxacin in experimentally induced pseudomonas pneumonia in neutropenic guinea pigs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1985; 27: 452–4

Michea-Hamzehpour M, Auckenthaler R, Regamey P, et al. Resistance occurring after fluoroquinolone therapy of experimental Pseudomonas aeruginosa peritonitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1987; 31: 1803–8

Drusano GL, Johnson DE, Rosen M, et al. Pharmacodynamics of a fluoroquinolone antimicrobial agent in a neutropenic rat model of Pseudomonas sepsis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1993; 37: 483–90

Schentag JJ, Nix DE, Adelman MH. Mathematical examination of dual individualization principles (I): relationships between AUC above MIC and area under the inhibitory curve for cefmenoxime, ciprofloxacin, and tobramycin. DICP Ann Pharmacother 1991; 25: 1050–7

Noone P, Parsons TMC, Pattison JR, et al. Experience in monitoring gentamicin therapy during treatment of serious gram-negative sepsis. BMJ 1974; 1: 477–81

Moore RD, Smith CR, Lietman PS. The association of aminoglycoside plasma levels with mortality in patients with Gram-negative bacteremia. J Infect Dis 1984; 149: 443–8

McCormack JP, Schentag JJ. Potential impact of quantitative susceptibility tests on the design of aminoglycoside dosing regimens. Drug Intell Clin Pharm 1987; 21: 187–91

Vogelman B, Gudmundsson S, Leggett J, et al. Correlation of antimicrobial pharmacokinetic parameters with therapeutic efficacy in an animal model. J Infect Dis 1988; 158: 831–47

Gerber AU, Brugger HP, Feller C, et al. Antibiotic therapy of infections due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa in normal and granulocytopenic mice: comparison of murine and human pharmacokinetics. J Infect Dis 1986; 153: 90–7

Gerber AU, Craig WA, Brugger HP, et al. Impact of dosing intervals on activity of gentamicin and ticarcillin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in granulocytopenic mice. J Infect Dis 1983; 147: 910–7

Zinner SH, Dudley MN, Blaser J. In vitro models in the study of combination antibiotic therapy in the neutropenic patient. Am J Med 1986; 80 Suppl 6B: 156–60

Bayer AS, Norman D, Kim KS. Efficacy of amikacin and ceftazidime in experimental aortic valve endocarditis due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1985; 8: 781–5

Barclay ML, Begg EJ, Hickling KG. What is the evidence for once-daily aminoglycoside therapy? Clin Pharmacokinet 1994; 27(1): 32–48

Craig WA, Redington J, Ebert SC. Pharmacodynamics of amikacin in vitro and in mouse thigh and lung infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 1991; 27 Suppl C: 29–40

Vogelman B, Gudmundsson S, Leggett J, et al. Correlation of antimicrobial pharmacokinetic parameters with therapeutic efficacy in an animal model. J Infect Dis 1988; 158: 831–47

Leggett J, Fantin B, Ebert S, et al. Comparative antibiotic doseeffect relations at several dosing intervals in murine pneumonitis and thigh-infection models. J Infect Dis 1989; 159: 281–92

Zhanel CG, Craig WA. Pharmacokinetic contributions to postantibiotic effects: focus on aminoglycosides. Clin Pharmacokinet 1994; 27(5): 377–92

Karlowsky JA, Zhanel GG, Davidson RJ, et al. In vitro postantibiotic effects following multiple exposures of cefotaxime, ciprofloxacin, and gentamicin against Escherichia coli in pooled human cerebrospinal fluid and Mueller-Hinton broth. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1993; 37: 1154–7

Moore RD, Smith CR, Lietman PS. Association of aminoglycoside plasma levels with therapeutic outcome in gram-negative pneumonia. Am J Med 1984; 77: 657–62

Moore RD, Lietman PS, Smith CR. Clinical response to aminoglycoside therapy: importance of the ratio of peak concentration to minimal inhibitory concentration. J Infect Dis 1987; 155: 93–9

Drusano GL. Human pharmacodynamics of β-lactams, aminoglycosides and their combination. Scand J Infect Dis 1991; 74 Suppl.: 235–48

Deziel-Evans LM, Murphy JE, Martin LJ. Correlation of pharmacokinetic indices with therapeutic outcome in patients receiving aminoglycosides. Clin Pharm 1986; 5: 319–24

Highet VS, Ballow CH, Forrest A. Population-derived AUIC is predictive of efficacy [abstract]. 95th American Society for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics: 1994 Mar 30 — Apr 1; New Orleans

Eagle H, Fleischman R, Musselman AD. Effect of schedule of administration on therapeutic efficacy of penicillin: importance of the aggregate time penicillin remains at effectively bactericidal levels. Am J Med 1950; 9: 280–99

Vogelman B, Craig WA. Kinetics of antimicrobial activity. J Pediatr 1986; 108: 835–40

Craig WA, Ebert SC. Killing and regrowth of bacteria in vitro: a review. Scand J Infect Dis 1991; 74 Suppl.: 63–70

White CA, Toothaker RD, Smith AL, et al. In vitro evaluation of the determinants of bactericidal activity of ampicillin dosing regimens against Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1989; 33: 1046–51

Schentag JJ, Smith IL, Swanson DJ, et al. Role for dual individualization with cefmenoxime. Am J Med 1984; 77 Suppl. 6A: 43–50

Grasso S, Meinardi G, de Carneri I, et al. New in vitro model to study the effect of antibiotic concentration and rate of elimination on antibacterial activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1978; 13: 570–6

Nishida M, Murakawa T, Kamimura T, et al. Bactericidal activity of cephalosporins in an in-vitro model simulating serum levels. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1978; 14: 6–12

Zinner SH, Dudley MN, Gilbert D, et al. Effect of dose and schedule on cefoperazone pharmacodynamics in an in-vitro model of infection in a neutropenic host. Am J Med 1988; 85 Suppl. 1A: 56–8

Onyeji CO, Nicolau DP, Nightingale CH, et al. Optimal times above MICs of ceftibuten and cefaclor in experimental intraabdominal infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1994; 38: 1112–7

Bodey GP, Ketchel SJ, Rodriguez V. A randomized study of carbenicillin plus cefamandole or tobramycin in the treatment of febrile episodes in cancer patients. Am J Med 1979; 67: 608–11

Edwards DJ, Pancorbo S. Routine monitoring of serum vancomycin concentrations: waiting for proof of its value. Clin Pharm 1987; 6: 652–4

Freeman CD, Quintiliani R, Nightingale CH. Vancomycin therapeutic drug monitoring: is it necessary? Ann Pharmacother 1993; 27: 594–8

Cantu TG, Yamanaka-Yuen NA, Lietman PS. Serum vancomycin concentrations: reappraisal of their clinical value. Clin Infect Dis 1994; 18: 533–43

Flandrois JP, Fardel G, Carret G. Early stages of in-vitro killing curve of LY 146032 and vancomycin for Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1988; 32: 454–7

Peetermans WE, Hoogeterp JJ, Hazekamp-Van Dokkum AM, et al. Antistaphylococcal activities of teicoplanin and vancomycin in-vitro and in an experimental infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1990; 34: 1869–74

Cantoni L, Glauser MP, Bille J. Comparative efficacy of daptomycin, vancomycin, and cloxacillin for the treatment of staphylococcus aureus endocarditis in rats and the role of test conditions in this determination. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1990; 34: 2348–53

Caillon J, Juvin ME, Rirault JL, et al. Bactericidal effect of daptomycin (LY 146032) compared with vancomycin and teicoplanin against gram-positive bacteria. Pathol Biol 1989; 37: 540–8

Chambers HF, Kennedy S. Effects of dosage, peak and trough concentrations in serum, protein binding, and bactericidal rate on efficacy of teicoplanin in a rabbit model of endocarditis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1990; 34: 510–4

Cantoni L, Wenger A, Glauser MP, et al. Comparative efficacy of amoxicillin-clavulanate, cloxacillin, and vancomycin against methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis in rats. J Infect Dis 1989; 159: 989–93

Schaad UB, McCracken Jr GH, Nelson JD. Clinical pharmacology and efficacy of vancomycin in pediatric patients. J Pediatr 1980; 96: 119–26

Louria DB, Kaminski T, Buchman J. Vancomycin in severe staphylococcal infections. Arch Intern Med 1961; 107: 225–40

Leport C, Perronne C, Massip P, et al. Evaluation of teicoplanin for treatment of endocarditis caused by gram-positive cocci in 20 patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1989; 33: 871–6

Klepser ME, Kang SL, McGrath BJ, et al. Influence of vancomycin serum concentration on the outcome of gram-positive infections. Presented at The American College of Clinical Pharmacy Annual Winter Meeting; 1994 Feb 6–9; San Diego

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hyatt, J.M., McKinnon, P.S., Zimmer, G.S. et al. The Importance of Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Surrogate Markers to Outcome. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 28, 143–160 (1995). https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-199528020-00005

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-199528020-00005