Abstract

We investigated the contractile roles of M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors in urinary bladder from streptozotocin-treated mice. Wild-type and M2 muscarinic receptor knockout (M2 KO) mice were given a single injection of vehicle or streptozotocin (125 mg kg−1) 2–24 weeks prior to bladder assays. The effect of forskolin on contractions elicited to the muscarinic agonist, oxotremorine-M, was measured in isolated urinary bladder (intact or denuded of urothelium). Denuded urinary bladder from vehicle-treated wild-type and M2 KO mice exhibited similar contractile responses to oxotremorine-M, when contraction was normalized relative to that elicited by KCl (50 mM). Eight to 9 weeks after streptozotocin treatment, the EC50 value of oxotremorine-M increased 3.1-fold in urinary bladder from the M2 KO mouse (N = 5) compared to wild type (N = 6; P < 0.001). Analogous changes were observed in intact bladder. In denuded urinary bladder from vehicle-treated mice, forskolin (5 µM) caused a much greater inhibition of contraction in M2 KO bladder compared to wild type. Following streptozotocin treatment, this forskolin effect increased 1.6-fold (P = 0.032). At the 20- to 24-week time point, the forskolin effect increased 1.7-fold for denuded as well as intact bladders (P = 0.036, 0.01, respectively). Although streptozotocin treatment inhibits M3 receptor-mediated contraction in denuded urinary bladder, muscarinic contractile function is maintained in wild-type bladder by enhanced M2 contractile function. M2 receptor activation opposes forskolin-induced relaxation of the urinary bladder, and this M2 function is enhanced following streptozotocin treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes is associated with an alteration in the contractility of urinary bladder smooth muscle in addition to the well-known increase in urinary frequency (Longhurst and Belis 1986; Latifpour et al. 1989; Michel and Barendrecht 2008). The two main neurotransmitters eliciting contraction in human and rodent urinary bladder are adenosine triphosphate and acetylcholine, which act on a ligand-gated ion channel (P2X receptor) and two G-protein-coupled receptors (M2 and M3 muscarinic), respectively (de Groat and Yoshimura 2001). A common approach for studying how the functions of these receptors change in diabetes mellitus is to examine their contractile roles in isolated urinary bladder from animals treated with streptozotocin (STZ).

Treatment with STZ causes a hypertrophy of the rat urinary bladder (Longhurst and Belis 1986; Latifpour et al. 1989) and an upregulation in M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors in the urothelium and smooth muscle (Tong and Cheng 2002; Tong et al. 2006; Cheng et al. 2007). Not surprisingly, the contractile response to muscarinic agonists in whole urinary bladder increases following STZ treatment (Kolta et al. 1985; Nsabimana and Ojewole 2008). To control for the STZ-induced hypertrophy, several investigators have normalized contraction relative to the cross-sectional area of the muscle strip or have measured contractions in strips of urinary bladder having a similar cross-sectional area. These studies have yielded conflicting reports, however, including an increase (Latifpour et al. 1989), a decrease (Longhurst and Belis 1986), and no change (Lincoln et al. 1984) in muscarinic agonist-induced contraction. Whether there are specific changes in the contractile functions of M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors in urinary bladder from STZ-treated rodents is unknown.

In smooth muscle from the urinary bladder and several other organs, the M2 receptor outnumbers the M3 by a ratio that is often at least four to one, yet its function at the level of contraction is less than obvious (Ehlert 2003a, b). For example, it has long been known that subtype-selective muscarinic antagonists inhibit contraction of the urinary bladder with a profile consistent with that of an M3 mechanism (Hegde and Eglen 1999). In addition, there is little loss of muscarinic agonist-induced contraction in isolated urinary bladder from the M2 muscarinic receptor knockout out (M2 KO) mouse (Matsui et al. 2000, 2002). In smooth muscle from the M3 KO mouse, muscarinic agonists elicit contraction, and this response is lost in the M2/M3 double KO mouse, indicating that the M2 receptor can mediate contraction. Although the potency of this response is high, its E max expressed relative to that of wild type is only 10% in urinary bladder and about 30% in ileum and the fundus of the stomach (Matsui et al. 2000; Stengel et al. 2002). Thus, experiments on the M3 KO mouse have revealed a small role for the M2 receptor in contraction. In guinea pig ileum, this high-potency M2 mechanism is absent (Griffin et al. 2009).

Part of the reason why the M2 receptor appears to have little role in the experiments described above can be explained by the nature of some of the Gi-signaling pathways of the M2 receptor in smooth muscle. Muscarinic activation of smooth muscle elicits a Ca2+-dependent nonselective cation conductance (I cat; Bolton 1979; Inoue 1991). This conductance is pertussis toxin-sensitive (Inoue and Isenberg 1990), and it is greatly inhibited in intestinal smooth muscle from either the M2 KO or the M3 KO mouse (Sakamoto et al. 2007). Muscarinic receptor activation indirectly stimulates a Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channel in smooth muscle from guinea pig trachea (Wade and Sims 1993) and many other organs, presumably through mobilization of Ca2+ by the M3 receptor. This conductance may represent an inhibitory-feedback mechanism to suppress excessive excitation of smooth muscle. Muscarinic receptor activation in canine colon (Cole and Sanders 1989) and many other types of smooth muscle also directly inhibits the BKCa channel, and this response is pertussis toxin-sensitive (Kume et al. 1995; Nakamura et al. 2002), which suggests a role for the M2 receptor. In rat urinary bladder, pertussis toxin-treatment and M2 selective antagonists inhibit the direct muscarinic suppression of BKCa (Nakamura et al. 2002). Both the M2 inhibition of the BKCa channel and the M2 stimulation of I cat are expected to be lost in the M3 KO mouse, because they are contingent upon Ca2+ mobilization triggered by M3 receptor activation. Perhaps this accounts for the near complete loss of muscarinic contractile function in urinary bladder from the M3 KO mouse. Obviously, this M2–M3 interaction mechanism cannot account for the residual M2 receptor-mediated contraction in the ileum and fundus of the stomach from the M3 KO mouse.

One might expect some decrease in muscarinic agonist-induced contraction in smooth muscle from the M2 KO mouse or from pertussis toxin-treated animals because of the loss of M2 conductance mechanisms just described. In most instances, however, this is not observed (Thomas and Ehlert 1994; Sawyer and Ehlert 1999; Ehlert 2003a). We have previously shown that the potency of the M2 enhancement mechanism in intestinal (Sawyer and Ehlert 1999; Ehlert 2003a) and urinary bladder (Ehlert et al. 2005, 2007) smooth muscle is less than that of the M3 contractile mechanism so that muscarinic contractions are already maximal at an agonist concentration that is too low to trigger M2 mechanisms. One exception is the mouse uterus where muscarinic agonist-induced contraction is greatly inhibited in the M2 KO mouse (Kitazawa et al. 2008).

In smooth muscle, cAMP mediates relaxation, and activation of the M2 receptor inhibits adenylate cyclase and the relaxation elicited by forskolin and activation of β-adrenoceptors in gastrointestinal and urinary bladder smooth muscle (Ehlert 2003b). The potency of muscarinic agonists for eliciting this response in the guinea pig ileum is actually greater than that for eliciting a direct contraction through the M3 receptor (Ostrom and Ehlert 1997). In bovine and guinea pig trachea, M2 receptor activation inhibits forskolin- but not isoproterenol-mediated relaxation, suggesting that the β-adrenoceptor mediates relaxation through a non-cAMP mechanism (Ostrom and Ehlert 1998).

The M3 receptor interacts with Gq to mediate phosphoinositide hydrolysis and direct contraction in smooth muscle (Ehlert 2003b). Both the effect on phosphoinositide hydrolysis and contraction are pertussis toxin-insensitive (Ehlert 2003b). While many Gq-linked receptors elicit contraction in smooth muscle, the source of Ca2+ for M3 receptor-mediated contractions is mainly extracellular through voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels (Bolger et al. 1983). How the M3 receptor triggers an influx of Ca2+ is unclear. Most of the older electrophysiological literature suggests that the initial depolarization occurs through I cat followed by an influx of Ca2+ through voltage-sensitive channels, but neither the activation of I cat nor the inhibition of BKCa channels can explain the potent muscarinic agonist-induced contraction of isolated smooth muscle because the latter is insensitive to pertussis toxin (Ehlert 2003b), whereas the former two ionic mechanisms are pertussis toxin-sensitive (see above).

Given the importance of the STZ model of diabetes, we undertook a study to determine how M2 and M3 receptor-mediated contractions are altered in isolated urinary bladder from STZ-treated mice. We observed an increase in M2 and a decrease in M3 receptor-mediated contractions in urinary bladder smooth muscle from STZ-treated mice. We also observed a similar phenomenon in urinary bladder with intact urothelium, although the results are more complicated because of changes in muscarinic function in the urothelium with STZ treatment.

Methods

Animals

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee. M2 muscarinic receptor knockout (M2 KO) mice were generated as previously described (Matsui et al. 2000, 2002). Male C57BL/6 wild-type (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Inc., Indianapolis, IN, USA) and M2 KO mice (2–3 months old, 18–30 g) were fasted for 4–6 h and then briefly anesthetized with isoflurane (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc., St. Joseph, MO, USA) before a single intraperitoneal injection with either vehicle (sodium citrate dihydrate, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) or 125 mg kg−1 of STZ (Sigma Aldrich Chemical, St. Louis, MO, USA) 2 to 24 weeks prior to experiments on isolated bladder. Water containing 10% sucrose was given to animals 48 h after injection to prevent hypoglycemic shock. All mice were housed in a 12-h light/dark facility with free access to water and food. Blood glucose was measured using an Ascensia Contour glucometer (Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany), and diabetic ketoacidosis was assessed by Keto-Diastix (Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany). Heparinized saline was used to dilute and estimate blood glucose levels above the 600-mg/dL glucometer limit.

Isolated urinary bladder

Whole mouse urinary bladder was removed and cut in half sagittally. The urothelium was carefully dissected from one of the strips, while the other was left intact. Half-bladder strips were mounted in an organ bath in a longitudinal orientation and connected to a force-displacement transducer using silk thread. Tissues were immersed in a Krebs–Ringer bicarbonate buffer (124 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.3 mM MgSO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.8 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM glucose) at 37°C and gassed with O2/CO2 (19:1) as previously described (Ehlert et al. 2005). Resting tension was adjusted to a load of 1 g (9.8 mN) during an equilibration period of at least 1 h. Contractile responses were first generated by two test doses of KCl (50 mM). Bladder was washed and allowed to rest for 10 min after each test dose. The contractile response to KCl was calculated as the stable plateau value after a 3-min period minus the initial resting tension. Responses to other agents were either expressed in millinewton of force or normalized relative to the larger of the two responses to KCl, which were usually similar.

Contraction of the urinary bladder to the highly efficacious muscarinic agonist, oxotremorine-M, was measured using a cumulative technique. Each aliquot of the agonist was added to the bath, and the response was calculated as the stable plateau achieved within approximately 1 min minus the initial resting tension. Figure 1 shows a representative recording with the arrows indicating the final cumulative concentrations of agonist. After a complete concentration–response curve was measured, tissues were washed five to eight times over a period of 35–45 min before measurement of another curve. This initial concentration–response curve was not utilized but enabled the bladder to equilibrate and to achieve a maximal contractile state. Subsequent responses were recorded in a similar manner and are described under “Results” section.

Contractile response of denuded urinary bladder to oxotremorine-M measured using a cumulative technique. The urinary bladder was from a wild-type mouse that had been treated with streptozotocin approximately 20 weeks prior. Force of contraction of this representative experiment is plotted against time. The arrows indicate when aliquots of oxotremorine-M were added to the tissue bath. The final, cumulative concentration of oxotremorine-M is indicated beneath each arrow

Analysis of oxotremorine-M concentration–response curves

The maximal response (E max) and concentration of agonist eliciting half-maximal response (EC50) were estimated from the concentration–response curve using nonlinear regression analysis with Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

To estimate the potential loss of function in the M2 KO mouse bladder relative to wild type, we fitted the concentration–response curves from wild-type and M2 KO mice to Eqs. 1 and 2, respectively:

In both of these equations, EC50 and E max represent the corresponding estimates for wild-type tissue, y represents the measured contraction, X represents the concentration of oxotremorine-M, and n represents the Hill slope. In Eq. 2, δ represents the change in E max, and γ represents the scalar change in EC50 between wild type and M2 KO. For each treatment (i.e., vehicle or STZ), the concentration–response curves were fitted simultaneously to Eqs. 1 and 2 sharing the estimate of E max and EC50 between wild type and M2 KO and obtaining unique estimates of n for both wild type and M2 KO and unique estimates of δ and γ for the M2KO. To test for differences between bladders from vehicle- and STZ-treated animals, we determined the significance of the increase in residual variance when the estimate of δ or γ was shared between the vehicle- and STZ-treated groups as described by Motulsky and Christopoulos (2003).

We used the operational model (Black and Leff 1983) to quantify the effect of forskolin on the concentration–response curve to oxotremorine-M:

In this equation, y represents the measured contraction, X represents the concentration of oxotremorine-M, M sys represents the maximum response of the system, K represents the observed dissociation constant, m represents the transducer slope factor, and τ represents a parameter related to coupling efficiency. Specifically, the value of τ is proportional to the intrinsic efficacy of the agonist (ε), the amount of potentially active receptors (R T ), and the sensitivity of the signaling cascade (1/K E ). In our experiments, forskolin either caused a shift to the right or both a shift to the right and a decrease in the E max of the concentration–response curve. Both situations were adequately described by a reduction in the τ parameter of the operational model. The effects of forskolin on the two disparate parameters, EC 50 and E max, could be adequately described, therefore, by a decrease in the value of a single parameter (τ) that accurately accounts for the inhibitory effect of cAMP on the contractile elements (i.e., decrease in 1/K E ).

To quantify this effect in bladder from the wild-type mouse, we analyzed the control concentration–response curve using Eq. 3 and that measured in the presence of forskolin using an identical equation, but with the parameter τ replaced with the product, ατ:

The parameter α, therefore, represents the factor by which forskolin reduces the sensitivity of the signaling pathway for contraction.

To investigate how the M2 receptor opposes forskolin-induced relaxation, we compared the relaxant effect of forskolin in urinary bladder from wild-type and M2 KO mice. The control concentration–response curve in the M2 KO mouse was analyzed using Eq. 3 and that in the presence of forskolin was analyzed using an identical equation, but with the parameter τ replaced with the product, αβτ:

Here, β represents the relative difference, expressed as a factor, between the effect of forskolin in wild-type (α) and M2 KO mice (αβ). This parameter, therefore, is a measure of the role of the M2 receptor in opposing forskolin-induced relaxation—the smaller the value of β (or alternatively, the larger the value of −log β), the greater the role of the M2 receptor.

To estimate β, the concentration–response curves in the absence (control) and presence of forskolin and in both wild-type and M2 KO mice were fitted simultaneously to Eqs. 3, 4, and 5 to obtain unique estimates of M sys, m, α, and β (global nonlinear regression analysis). The estimate of τ was shared among the curves and that of K was shared between those of control and forskolin conditions. Figure 2 shows a pictorial representation of our analysis, and the legend describes additional details.

Determination of the role of the M2 receptor in opposing forskolin-induced relaxation. a The plot shows a simulation of a concentration–response curve to a muscarinic agonist in the absence (control) and presence of forskolin. The operational model (Eq. 3) was used to simulate the data. All of the parameters were the same for the two curves except that the parameter τ for the curve measured in the presence of forskolin was reduced to one tenth that of the control curve. The values of the parameters in the simulation were M sys = 100, m = 1.65, K = 106, and τ = 15. b The simulation illustrates the effect of forskolin on the concentration–response curve to a muscarinic agonist in smooth muscle from wild-type and M2 KO animals. For the wild-type curves, the effect of forskolin has been simulated by reducing the value of τ by the factor α. In other words, Eqs. 3 and 4 were used to simulate the control and forskolin conditions, respectively, with the value of α set to 0.48 in Eq. 4 and the values of all of the other parameters the same for the two equations. For the M2 KO curves, the effect of forskolin has been simulated by reducing τ by the factor αβ, with α = 0.48 as in wild type and β = 0.16. It follows that the log difference in the effect of forskolin in wild type (log α) and M2 KO (log αβ) is equivalent to log β. The values of the parameters for the simulations were, wild-type control, M sys = 100, m = 1.65, K = 106, and τ = 18; wild-type forskolin, same as control with α = 0.48; M2 KO control, same as wild type but with log τ = 15; M2 KO forskolin, same as M2 KO but with αβ = 0.078. c The plot shows that the role of the M2 receptor in opposing forskolin-induced relaxation (log β) is equivalent to the difference between the relaxant effect of forskolin in wild type (log α) and M2 KO (log αβ). The values of α and β are the same as those used in the simulation in (b)

The statistical significance of differences between parameter estimates measured in urinary bladders from vehicle- and STZ-treated mice was determined as described above in connection with Eqs. 1 and 2.

Results

Effects of STZ on body weight and blood glucose

Wild-type and M2 KO mice injected with a single dose (125 mg kg−1) of STZ exhibited significantly higher fasting blood glucose levels compared to control animals (Table 1). Body weight decreased significantly more in STZ-treated mice compared to those treated with vehicle with the exception of wild-type mice at the 2- to 3-week time point (Table 1). Although STZ significantly decreased the weight of M2 KO compared to wild-type mice at 8 to 9 weeks (Table 1), denuded bladder tissue from these animals did not exhibit a difference in KCl-induced contraction (data not shown).

Effects of STZ on denuded urinary bladder

Muscarinic agonist-induced contractions

Two to 3 weeks after treatment with STZ, wild-type urinary bladder lacking urothelium (denuded) displayed a slight decrease in contractile responsiveness to oxotremorine-M as compared to tissue from vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 3a). At both the 8–9- and 20–24-week time points after STZ treatment, however, the E max values of oxotremorine-M in denuded bladders were markedly greater than those from vehicle-treated animals (Fig. 3d, g). These effects were manifest mainly as significant 58% and 61% increases in E max when expressed in units of force (millinewton; Table 2). These data illustrate a time-dependent increase of contractile response in tissues from STZ-treated mice.

Effect of streptozotocin (STZ) treatment on oxotremorine-M-mediated contractions in urinary bladder lacking urothelium from wild-type and M2 KO mice. Concentration–response curves were measured 2 to 3 weeks (a–c), 8 to 9 weeks (d–f), and 20 to 24 weeks (g–i) after STZ treatment in urinary bladder from wild-type (a, b, d, e, g, h) and M2 KO (c, f, i) mice. Contractions are expressed in units of force (millinewton; a, d, g) or relative to the contraction elicited by KCl (50 mM; b, c, e, f, h, i). Circles denote the vehicle-treated group; triangles denote the STZ-treated group. Mean ± SEM values from three to seven experiments are shown, each done on a separate bladder

When normalized relative to the contraction elicited by KCl (50 mM), however, the concentration–response curves in bladder from wild-type mice showed little difference between vehicle and STZ groups at all time points (Fig. 3b, e, h and Table 2), suggesting that STZ treatment might cause smooth muscle hypertrophy or a general increase in contractility over time. In experiments on urinary bladder from M2 KO mice, there was little difference between vehicle and STZ groups at the early (2–3 weeks) and late (20–24 weeks) time points (Fig. 3c, i). At the intermediate time point (8–9 weeks), STZ treatment caused a significant loss of contractile function (Fig. 3f), which was manifest as a significant 2.3-fold increase in EC50 (Table 2).

To quantify the role of the M2 receptor, we compared the loss of contractile function in the M2 KO mouse relative to wild type. In vehicle-treated mice, there was little difference in the contractile activity of oxotremorine-M in urinary bladder from wild-type and M2 KO mice. Similarly, there was little difference in contractile activity between wild-type and M2 KO mice at the early (2–3 weeks) and late (20–24 weeks) time points after STZ treatment. At the intermediate time point (8–9 weeks), however, STZ induced a greater loss of function in urinary bladder from the M2 KO mouse (Fig. 3f) compared to that from wild type (Fig. 3e), which was manifest as a 3.1-fold increase in EC50 (log shift in EC50 = 0.49 ± 0.055; F = 21.30, P < 0.001). Since muscarinic contractile function is absent in urinary bladder from M2/M3 double KO mice (Matsui et al. 2002), these data indicate that STZ treatment inhibits M3 receptor-mediated contraction and that this response is restored by the M2 receptor.

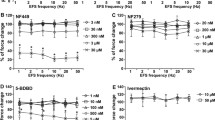

M2 muscarinic receptor-mediated inhibition of forskolin-induced relaxation

We investigated the effect of prior treatment with STZ on forskolin-induced inhibition of contraction to oxotremorine-M in denuded urinary bladder from wild-type and M2 KO mice. Forskolin (5 µM) had a small inhibitory effect on the concentration–response curve to oxotremorine-M in wild-type bladder from vehicle- and STZ-treated mice at all time points (Fig. 4). A much greater effect was observed in denuded bladder from M2 KO mice, which is consistent with the role of the M2 receptor in opposing adenylate cyclase-mediated inhibition of contraction.

Effect of streptozotocin (STZ)-treatment on M2 receptor-mediated inhibition of relaxation in urinary bladder lacking urothelium. The effect of forskolin (5 µM) on oxotremorine-M-mediated contractile responses was measured in wild-type and M2 KO bladders 2 to 3 weeks (a, b), 8 to 9 weeks (c–d), and 20 to 24 weeks (e–f) after STZ treatment. Open circles denote wild type, control; closed circles denote wild type in the presence of forskolin; open triangles denote M2 KO, control; closed triangles denote M2 KO in the presence of forskolin. Mean ± SEM values from three to seven experiments are indicated, each done on a separate bladder

We used the operational model (see “Methods” section) to estimate the relaxant effect of forskolin in urinary bladder from wild-type (−log α) and M2 KO (−log αβ) mice. The difference between these two estimates (−log β) is a measure of the function of the M2 receptor in opposing forskolin-induced relaxation. The −log β values were estimated in urinary bladder from vehicle- and STZ-treated mice at the three time points, and the results are summarized in Fig. 5a. At the 8–9- and 20–24-week time points, STZ treatment caused a significant increase in the role of the M2 receptor in opposing the relaxant effect of forskolin.

Effect of streptozotocin treatment on the role of the M2 receptor in opposing forskolin-induced relaxation in denuded (a) and intact (b) urinary bladder. The function of the M2 receptor is quantified as the parameter −log β, which is defined as the difference between the effect of forskolin in urinary bladders from wild-type (−log α) and M2 KO (−log αβ) mice as described under “Methods” section. The parameters were estimated from the data in Figs. 4 and 7. * Significantly different from vehicle, P < 0.05

Effects of STZ on intact urinary bladder

Muscarinic agonist-induced contractions

The presence of urothelium caused a modest change in the contractile activity of oxotremorine-M in the urinary bladder (Fig. 6). The overall average E max value of oxotremorine-M in intact, wild-type urinary bladder from all of the vehicle-treated groups (201.9 ± 8.9%, KCl-normalized contraction, Fig. 6b, e, h) was significantly smaller than the corresponding estimate for denuded urinary bladder (243.4 ± 11.6%, KCl-normalized contraction, Fig. 3b, e, h; F = 8.82; P = 0.0033). There was little or no difference in the contractile activity of oxotremorine-M in denuded bladder from vehicle-treated wild-type and M2 KO mice at all time points (Fig. 3). In contrast, the overall average EC50 value of oxotremorine-M in intact, M2 KO urinary bladder from all of the vehicle-treated groups (pEC50 = 6.38 ± 0.13) was significantly greater (lower potency) than the corresponding estimate for wild-type bladder (pEC50 = 6.84 ± 0.055; Fig. 6; F = 16.029, P < 0.001).

Effect of streptozotocin (STZ) treatment on oxotremorine-M-mediated contractions in urinary bladder with intact urothelium from wild-type and M2 KO mice. Concentration–response curves were measured 2 to 3 weeks (a–c), 8 to 9 weeks (d–f), and 20 to 24 weeks (g–i) after STZ treatment in urinary bladder from wild-type (a, b, d, e, g, h) and M2 KO (c, f, i) mice. Contractions are expressed in units of force (millinewton; a, d, g) or relative to the contraction elicited by KCl (50 mM; b, c, e, f, h, i). Circles denote the vehicle-treated group; triangles denote the STZ-treated group. Mean ± SEM values from three to seven experiments are shown, each done on a separate bladder

Eight to 9 weeks after STZ treatment, the E max value of oxotremorine-M, expressed in millinewton, was significantly greater by 51% in intact urinary bladder from STZ-treated wild-type mice compared to intact bladder from vehicle-treated wild-type animals (Fig. 6d and Table 3). When contraction was normalized relative to that elicited by KCl (50 mM; Fig. 6e), this difference persisted (Table 3). STZ treatment (8 to 9 weeks prior) had no effect on the contractile action of oxotremorine-M in intact urinary bladder from the M2 KO mouse (Fig. 6f). Nonetheless, when the activity of oxotremorine-M in the intact M2 KO bladder is compared to that of wild type, there is a greater reduction in E max following STZ treatment (F = 5.11, P = 0.026).

These changes were not significant 2 to 3 weeks (Fig. 6a–c) or 20 to 24 weeks (Fig. 6g–i) after STZ treatment.

M2 muscarinic receptor-mediated inhibition of forskolin-induced relaxation

We also investigated M2 receptor-mediated inhibition of relaxation in urinary bladder with intact urothelium (Fig. 7). As observed in denuded bladder, the relaxant effect of forskolin on oxotremorine-M-induced contractions was greater in intact urinary bladder from the M2 KO mouse compared to that from wild type, illustrating the role of the M2 receptor in opposing the relaxant effect of forskolin. This action of the M2 receptor was significantly enhanced 2 to 3 weeks and 20 to 24 weeks after STZ treatment (Fig. 5b).

Effect of streptozotocin (STZ)-treatment on M2 receptor-mediated inhibition of relaxation in urinary bladder with intact urothelium. The effect of forskolin (5 µM) on oxotremorine-M-mediated contractile responses was measured in wild-type and M2 KO bladders 2 to 3 weeks (a, b), 8 to 9 weeks (c, d), and 20 to 24 weeks (e, f) after STZ treatment. Open circles denote wild type, control; closed circles denote wild type in the presence of forskolin; open triangles denote M2 KO, control; closed triangles denote M2 KO in the presence of forskolin. Mean ± SEM values from three to seven experiments are indicated, each done on a separate bladder

Discussion and conclusions

In our study, we used a single injection of STZ (125 mg kg−1) to induce diabetes. This dose was determined to yield maximal levels of hyperglycemia with minimal mortality (data not shown). High doses of STZ (≥200 mg kg−1) promote nonspecific cytotoxicity and acute renal tubular damage (Tay et al. 2005). When moderate doses (100–125 mg kg−1) are used on two consecutive days, nonspecific and acute renal cytotoxicity is markedly reduced, and mice develop renal injury biochemically and histologically similar (albeit less severe) to human nephropathy (Tesch and Nikolic-Paterson 2006; Tesch and Allen 2007), which can develop as a late diabetic complication after 10–20 years (Molitch et al. 2004). Our use of a single injection of STZ (125 mg kg−1) probably caused even less STZ-induced nonspecific and acute cytotoxicity. Also, it is unlikely that our mice suffered from diabetic ketoacidosis as urinalysis test strips showed zero, or very rarely, trace (5 mg dL−1) amounts of acetoacetic acid in animals treated with STZ at all time points (data not shown). We found that M3 KO mice were very sensitive to STZ, and none survived long enough for experiments. M3 KO mice of a C57BL/6 genetic background exhibit impaired glucose tolerance (Gautam et al. 2006), which may contribute to their high sensitivity to STZ.

We observed that STZ inhibits M2 KO but not wild-type bladder contraction 8 to 9 weeks after treatment (Fig. 3e, f), suggesting that the M2 receptor rescues impaired M3 receptor-mediated contraction in denuded diabetic bladder. Mimata et al. (1995) observed a 30% increase in carbachol-stimulated phosphoinositide hydrolysis in [3H]inositol-labeled diabetic rat bladder when this response was expressed as the conversion of labeled [3H]phosphoinositides into [3H]inositol phosphates. Since the M3 receptor is known to mediate phosphoinositide hydrolysis in mouse urinary bladder (Tran et al. 2006), the results of Mimata et al. (1995) suggest an increase in M3 function in diabetic bladder. Perhaps this increase might contribute to the overall increase in muscarinic receptor-induced contractile force (millinewton) that we observed in wild-type mouse urinary bladder. Most of this increase in contraction can be attributed to the M2 receptor, however, which does not signal through phosphoinositide hydrolysis in mouse urinary bladder (Tran et al. 2006). Also, the increase in muscarinic contractile force was absent when contractions were normalized relative to that elicited by KCl. Alternatively, there may be differences in the effects of STZ on urinary bladder from rats and mice.

Previous work from our lab has shown that the M2 receptor enhances contractions elicited by the M3 receptor in colon (Sawyer and Ehlert 1999) and urinary bladder (Ehlert et al. 2005) from normal guinea pig and mouse, respectively. This M2 enhancement mechanism acts at a lower potency than that required for M3-mediated contractions, and oxotremorine-M elicits a maximal contraction through the M3 receptor at a concentration that is too low to activate the M2 enhancement function (Sawyer and Ehlert 1999; Ehlert et al. 2005). When a portion of the population of M3 receptors is pharmacologically inactivated, oxotremorine-M is still able to elicit maximal contraction, albeit at a 20-fold lower potency. In these bladders, inhibition of M2 receptor signaling by pertussis toxin (Sawyer and Ehlert 1999) or by gene deletion (Ehlert et al. 2005) induces a substantial loss of function in urinary bladder, revealing M2 enhancement of contractions elicited by the M3 receptor. Since the M3 receptor can elicit a maximal contraction on its own, the normal physiological significance for the M2 enhancement mechanism is unclear, but the observation in the current study that this mechanism rescues M3 receptor-mediated contractions, which have been attenuated by STZ treatment, may suggest that the M2 receptor has a crucial role in sustaining function in disease states such as diabetes.

A similar upregulation in M2 receptor function occurs with denervation of the urinary bladder or obstruction of its outlet. In the rat model of these conditions, there is an upregulation of M2 muscarinic receptor expression and mRNA, an increase in the potency of muscarinic agonists for eliciting contraction, and a change in the potency of antagonists for inhibiting contraction that is consistent with a greater role for the M2 receptor (Braverman et al. 1998, 1999). This increase in M2 function is caused by hypertrophy of the bladder because the increase in M2 receptor expression is prevented in rats that have had their ureters sutured to the colon to divert the flow of urine to the GI tract and prevent the denervation-induced distension and hypertrophy of the bladder (Braverman and Ruggieri 2003). An analogous increase in M2 function has been observed in human urinary bladder with reduced innervation as a result of spinal injury (Pontari et al. 2004; Ruggieri and Braverman 2006).

Another role of the M2 receptor involves inhibition of cAMP-mediated relaxation in smooth muscle from mouse (Matsui et al. 2003; Ehlert et al. 2005, 2007), guinea pig (Noronha-Blob et al. 1989; Thomas et al. 1993), and rat (Hegde et al. 1997). In the current study, we investigated how STZ treatment affects this M2 receptor-mediated disinhibition of contraction by comparing the degree of forskolin-induced inhibition of muscarinic contractions in M2 KO versus wild-type bladders. Forskolin had a greater effect on the concentration–response curve to oxotremorine-M (i.e., rightward shift) in bladder from M2 KO mice compared to that from wild-type animals, illustrating the ability of the M2 receptor to oppose the relaxant effect of forskolin. This M2 disinhibition of contraction was significantly greater at the intermediate (8–9 weeks) and long (20–24 weeks) time points after STZ treatment in denuded urinary bladders (Fig. 5a). These data are consistent with the observation that STZ treatment increases M2 receptor expression (Tong et al. 1999, 2002a, b, 2006; Stevens et al. 2006) in bladder smooth muscle.

Urothelium is known to release an inhibitory factor upon muscarinic stimulation (Hawthorn et al. 2000; Kosan et al. 2005). Our results are consistent with this phenomenon, because we found that oxotremorine-M exhibited a significantly greater E max value for contraction in denuded wild type compared to intact wild type urinary bladder. We also found that while there was no difference in the contractile activity of oxotremorine-M in denuded bladder from wild-type and M2 KO mice, the agonist did exhibit 2.9-fold lower potency in intact M2 KO relative to intact wild-type urinary bladder. Previously, we reported a similar difference in intact bladder (Matsui et al. 2003). These results might suggest that urothelial M2 receptors mediate an inhibition of the release of the inhibitory factor, whose initial release is stimulated by a muscarinic subtype other than M2. The human urothelium expresses mRNA for all muscarinic subtypes, with M2 mRNA greatly exceeding that of the other subtypes (Bschleipfer et al. 2007). Urothelial M2 (Tong et al. 2006) and M3 (Cheng et al. 2007) receptor expression is upregulated with STZ treatment. The urothelium is now known to be more involved in bladder function beyond its traditional role as a passive barrier to underlying smooth muscle (Birder and de Groat 2007).

The inhibitory effect of the urothelium on muscarinic contractility is abolished by STZ treatment in rats, suggesting a loss in release of the inhibitory factor (Kosan et al. 2005). We also confirmed that STZ treatment enhanced contractions in intact wild-type mouse urinary bladder (Fig. 6e), but had no effect on denuded wild-type bladder when contraction was normalized relative to KCl (Fig. 3e).

In denuded M2 KO bladder (Fig. 3f), we found that STZ treatment inhibited muscarinic contractile potency, whereas in intact M2 KO bladder (Fig. 6f), STZ treatment had no effect. This seemingly conflicting result can be explained by the opposing effects of STZ treatment on muscarinic contractility in intact M2 KO urinary bladder—an enhancement from the loss of urothelial inhibition and an inhibition from a loss of M3 function. The loss of M3 function was manifest in intact urinary bladder as a significant reduction in the E max of oxotremorine-M in M2 KO relative to wild type 8 to 9 weeks after STZ treatment. This loss of function was significantly greater than that observed in intact bladder from vehicle-treated animals. Thus, our hypothesis that STZ treatment inhibits M3 receptor contractile function in smooth muscle and that the smooth muscle M2 receptor rescues contractile function is supported by our findings on both denuded and intact bladder 8 to 9 weeks after STZ treatment. This effect seems to be short-lived, however, because it is lost 20 to 24 weeks after STZ treatment.

Our experiments on the role of the M2 receptor in opposing forskolin-induced relaxation in intact bladders showed an increase in this function following STZ treatment. We observed a significant increase in M2 function at the early (2–3 weeks) and late (20–24 weeks) time points after STZ treatment, but not at the intermediate time point (8–9 weeks). In denuded bladder, significant differences were measured at the intermediate and late time points. We have no explanation for this difference, but experimental variation and changes in the effect of forskolin on the release of mediators from the urothelium after STZ treatment (Birder et al. 2002) may confound our results.

This temporal progression of differential changes in M2 and M3 contractile function in urinary bladder is likely caused by gradual STZ-induced alterations. Hyperglycemia-induced neuronal dysfunction and subsequent damage to the neuromuscular junction may alter contractile function in smooth muscle. Additionally, the rich innervation of the urothelium (Wakabayashi et al. 1995) and its high level of glucose metabolism may make urothelial tissue gradually susceptible to diabetic conditions. Our results provide a clearer understanding of the differential roles of M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors in STZ-induced diabetes and how the M2 receptor maintains contractile function in this disease model.

References

Birder LA, de Groat WC (2007) Mechanisms of disease: involvement of the urothelium in bladder dysfunction. Nat Clin Pract Urol 4:46–54

Birder LA, Nealen ML, Kiss S, de Groat WC, Caterina MJ, Wang E, Apodaca G, Kanai AJ (2002) Beta-adrenoceptor agonists stimulate endothelial nitric oxide synthase in rat urinary bladder urothelial cells. J Neurosci 22:8063–8070

Black JW, Leff P (1983) Operational models of pharmacological agonism. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 220:141–162

Bolger GT, Gengo P, Klockowski R, Luchowski E, Siegel H, Janis RA, Triggle AM, Triggle DJ (1983) Characterization of binding of the Ca++ channel antagonist, [3H]nitrendipine, to guinea-pig ileal smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 225:291–309

Bolton TB (1979) Mechanisms of action of transmitters and other substances on smooth muscle. Physiol Rev 59:606–718

Braverman AS, Ruggieri MR Sr (2003) Hypertrophy changes the muscarinic receptor subtype mediating bladder contraction from M3 toward M2. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 285:R701–R708

Braverman AS, Luthin GR, Ruggieri MR (1998) M2 muscarinic receptor contributes to contraction of the denervated rat urinary bladder. Am J Physiol 275:R1654–R1660

Braverman A, Legos J, Young W, Luthin G, Ruggieri M (1999) M2 receptors in genito-urinary smooth muscle pathology. Life Sci 64:429–436

Bschleipfer T, Schukowski K, Weidner W, Grando SA, Schwantes U, Kummer W, Lips KS (2007) Expression and distribution of cholinergic receptors in the human urothelium. Life Sci 80:2303–2307

Cheng J-T, Yu B-C, Tong Y-C (2007) Changes of M3-muscarinic receptor protein and mRNA expressions in the bladder urothelium and muscle layer of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Neurosci Lett 423:1–5

Cole WC, Sanders KM (1989) G proteins mediate suppression of Ca2 + -activated K current by acetylcholine in smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol 257:C596–C600

de Groat WC, Yoshimura N (2001) Pharmacology of the lower urinary tract. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 41:691–721

Ehlert FJ (2003a) Pharmacological analysis of the contractile role of M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors in smooth muscle. Receptors Channels 9:261–277

Ehlert FJ (2003b) Contractile role of M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors in gastrointestinal, airway and urinary bladder smooth muscle. Life Sci 74:355–366

Ehlert FJ, Griffin MT, Abe DM, Vo TH, Taketo MM, Manabe T, Matsui M (2005) The M2 muscarinic receptor mediates contraction through indirect mechanisms in mouse urinary bladder. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 313:368–378

Ehlert FJ, Ahn S, Pak KJ, Park GJ, Sangnil MS, Tran JA, Matsui M (2007) Neuronally released acetylcholine acts on the m2 muscarinic receptor to oppose the relaxant effect of isoproterenol on cholinergic contractions in mouse urinary bladder. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 322:631–637

Gautam D, Han S-J, Hamdan FF, Jeon J, Li B, Li JH, Cui Y, Mears D, Lu H, Deng C, Heard T, Wess J (2006) A critical role for [beta] cell M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in regulating insulin release and blood glucose homeostasis in vivo. Cell Metabolism 3:449–461

Griffin MT, Matsui M, Ostrom RS, Ehlert FJ (2009) The guinea pig ileum lacks the direct, high-potency, M(2)-muscarinic, contractile mechanism characteristic of the mouse ileum. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 380:327–335

Hawthorn MH, Chapple CR, Cock M, Chess-Williams R (2000) Urothelium-derived inhibitory factor(s) influences on detrusor muscle contractility in vitro. Br J Pharmacol 129:416–419

Hegde SS, Eglen RM (1999) Muscarinic receptor subtypes modulating smooth muscle contractility in the urinary bladder. Life Sci 64:419–428

Hegde SS, Choppin A, Bonhaus D, Briaud S, Loeb M, Moy TM, Loury D, Eglen RM (1997) Functional role of M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors in the urinary bladder of rats in vitro and in vivo. Br J Pharmacol 120:1409–1418

Inoue R (1991) Ion channels involved in responses to muscarinic receptor activation in smooth muscle. In: Sperelakis HKN (ed) Ion channels of vascular smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells. Elsevier Science Publishing Co., Inc, New York, pp 81–91

Inoue R, Isenberg G (1990) Acetylcholine activates nonselective cation channels in guinea pig ileum through a G protein. Am J Physiol 258:C1173–C1178

Kitazawa T, Hirama R, Masunaga K, Nakamura T, Asakawa K, Cao J, Teraoka H, Unno T, Komori S, Yamada M, Wess J, Taneike T (2008) Muscarinic receptor subtypes involved in carbachol-induced contraction of mouse uterine smooth muscle. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 377:503–513

Kolta MG, Wallace LJ, Gerald MC (1985) Streptozocin-induced diabetes affects rat urinary bladder response to autonomic agents. Diabetes 34:917–921

Kosan M, Hafez G, Ozturk B, Ozgunes O, Gur S, Cetinkaya M (2005) Effect of urothelium on bladder contractility in diabetic rats. Int J Urol 12:677–682

Kume H, Mikawa K, Takagi K, Kotlikoff MI (1995) Role of G proteins and KCa channels in the muscarinic and beta-adrenergic regulation of airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol 268:L221–L229

Latifpour J, Gousse A, Kondo S, Morita T, Weiss RM (1989) Effects of experimental diabetes on biochemical and functional characteristics of bladder muscarinic receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 248:81–88

Lincoln J, Crockett M, Haven AJ, Burnstock G (1984) Rat bladder in the early stages of streptozotocin-induced diabetes: adrenergic and cholinergic innervation. Diabetologia 26:81–87

Longhurst PA, Belis JA (1986) Abnormalities of rat bladder contractility in streptozotocin-induced diabetes mellitus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 238:773–777

Matsui M, Motomura D, Karasawa H, Fujikawa T, Jiang J, Komiya Y, Takahashi S, Taketo MM (2000) Multiple functional defects in peripheral autonomic organs in mice lacking muscarinic acetylcholine receptor gene for the M3 subtype. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:9579–9584

Matsui M, Motomura D, Fujikawa T, Jiang J, Takahashi S, Manabe T, Taketo MM (2002) Mice lacking M2 and M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors are devoid of cholinergic smooth muscle contractions but still viable. J Neurosci 22:10627–10632

Matsui M, Griffin MT, Shehnaz D, Taketo MM, Ehlert FJ (2003) Increased relaxant action of forskolin and isoproterenol against muscarinic agonist-induced contractions in smooth muscle from M2 receptor knockout mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 305:106–113

Michel MC, Barendrecht MM (2008) Physiological and pathological regulation of the autonomic control of urinary bladder contractility. Pharmacol Ther 117:297–312

Mimata H, Wheeler MA, Fukomoto Y, Takigawa H, Nishimoto T, Weiss RM, Latifpour J (1995) Enhancement of muscarinic receptor-coupled phosphatidylinositol hydrolysis in diabetic bladder. Mol Cell Biochem 152:71–76

Molitch ME, DeFronzo RA, Franz MJ, Keane WF, Mogensen CE, Parving HH, Steffes MW (2004) Nephropathy in diabetes. Diabetes Care 27(Suppl 1):S79–S83

Motulsky H, Christopoulos A (2003) Fitting models to biological data using linear and nonlinear regression. GraphPad Software, Inc, San Diego

Nakamura T, Kimura J, Yamaguchi O (2002) Muscarinic M2 receptors inhibit Ca2 + -activated K + channels in rat bladder smooth muscle. Int J Urol 9:689–696

Noronha-Blob L, Lowe V, Patton A, Canning B, Costello D, Kinnier WJ (1989) Muscarinic receptors: relationships among phosphoinositide breakdown, adenylate cyclase inhibition, in vitro detrusor muscle contractions and in vivo cystometrogram studies in guinea pig bladder. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 249:843–851

Nsabimana AM, Ojewole JA (2008) Diabetes mellitus and responses of the urinary bladder to acetylcholine: an in vitro study. J Smooth Muscle Res 44:143–150

Ostrom RS, Ehlert FJ (1997) M2 muscarinic receptor inhibition of agonist-induced cyclic adenosine monophosphate accumulation and relaxation in the guinea pig ileum. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 280:189–199

Ostrom RS, Ehlert FJ (1998) M2 muscarinic receptors inhibit forskolin-but not isoproterenol-mediated relaxation in bovine tracheal smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 286:234–242

Pontari MA, Braverman AS, Ruggieri MR Sr (2004) The M2 muscarinic receptor mediates in vitro bladder contractions from patients with neurogenic bladder dysfunction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 286:R874–R880

Ruggieri MR Sr, Braverman AS (2006) Regulation of bladder muscarinic receptor subtypes by experimental pathologies. Auton Autacoid Pharmacol 26:311–325

Sakamoto T, Unno T, Kitazawa T, Taneike T, Yamada M, Wess J, Nishimura M, Komori S (2007) Three distinct muscarinic signalling pathways for cationic channel activation in mouse gut smooth muscle cells. J Physiol 582:41–61

Sawyer GW, Ehlert FJ (1999) Muscarinic M3 receptor inactivation reveals a pertussis toxin-sensitive contractile response in the guinea pig colon: evidence for M2/M3 receptor interactions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 289:464–476

Stengel PW, Yamada M, Wess J, Cohen ML (2002) M(3)-receptor knockout mice: muscarinic receptor function in atria, stomach fundus, urinary bladder, and trachea. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 282:R1443–R1449

Stevens LA, Sellers DJ, McKay NG, Chapple CR, Chess-Williams R (2006) Muscarinic receptor function, density and G-protein coupling in the overactive diabetic rat bladder. Auton Autacoid Pharmacol 26:303–309

Tay YC, Wang Y, Kairaitis L, Rangan GK, Zhang C, Harris DC (2005) Can murine diabetic nephropathy be separated from superimposed acute renal failure? Kidney Int 68:391–398

Tesch GH, Allen TJ (2007) Rodent models of streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy. Nephrology (Carlton) 12:261–266

Tesch GH, Nikolic-Paterson DJ (2006) Recent insights into experimental mouse models of diabetic nephropathy. Nephron Exp Nephrol 104:e57–e62

Thomas EA, Ehlert FJ (1994) Pertussis toxin blocks M2 muscarinic receptor-mediated effects on contraction and cyclic AMP in the guinea pig ileum, but not M3-mediated contractions and phosphoinositide hydrolysis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 271:1042–1050

Thomas EA, Baker SA, Ehlert FJ (1993) Functional role for the M2 muscarinic receptor in smooth muscle of guinea pig ileum. Mol Pharmacol 44:102–110

Tong YC, Cheng JT (2002) Alteration of M(3) subtype muscarinic receptors in the diabetic rat urinary bladder. Pharmacology 64:148–151

Tong YC, Chin WT, Cheng JT (1999) Alterations in urinary bladder M2-muscarinic receptor protein and mRNA in 2-week streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Neurosci Lett 277:173–176

Tong YC, Cheng JT, Wan WC (2002a) Effects of Ba-Wei-Die-Huang-Wan on the cholinergic function and protein expression of M2 muscarinic receptor of the urinary bladder in diabetic rats. Neurosci Lett 330:21–24

Tong YC, Chin WT, Cheng JT (2002b) Role of sorbitol in the up-regulation of urinary bladder M(2) muscarinic receptors in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Neurourol Urodyn 21:154–159

Tong Y-C, Cheng J-T, Hsu C-T (2006) Alterations of M2-muscarinic receptor protein and mRNA expression in the urothelium and muscle layer of the streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat urinary bladder. Neurosci Lett 406:216–221

Tran JA, Matsui M, Ehlert FJ (2006) Differential coupling of muscarinic M1, M2, and M3 receptors to phosphoinositide hydrolysis in urinary bladder and longitudinal muscle of the ileum of the mouse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 318:649–656

Wade GR, Sims SM (1993) Muscarinic stimulation of tracheal smooth muscle cells activates large-conductance Ca(2+)-dependent K + channel. Am J Physiol 265:C658–C665

Wakabayashi Y, Kojima Y, Makiura Y, Tomoyoshi T, Maeda T (1995) Acetylcholinesterase-positive afferent axons in mucosa of urinary bladder of adult cats: retrograde tracing and degeneration studies. Histol Histopathol 10:523–530

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Institutes of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) RO1 GM069829, University of Tennessee, federal flow through funds from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) UTN-37775, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Individual National Research Service Award Fellowship F30 DK081289, Achievement Rewards for College Scientists (ARCS) Foundation grant, and the UC Irvine Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the aforementioned funding sources. This work was also presented at the British Pharmacological Society Third Focused Meeting on Cell Signaling on April 21, 2009, at the University of Leicester, Leicester, UK.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pak, K.J., Ostrom, R.S., Matsui, M. et al. Impaired M3 and enhanced M2 muscarinic receptor contractile function in a streptozotocin model of mouse diabetic urinary bladder. Naunyn-Schmied Arch Pharmacol 381, 441–454 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-010-0509-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-010-0509-6